Page 172 - Contributed Paper Session (CPS) - Volume 8

P. 172

CPS2227 Jonathan Haughton

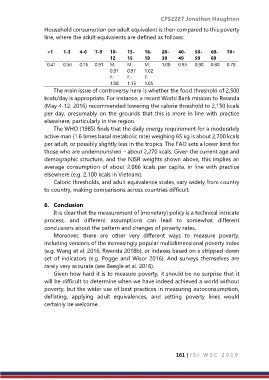

Household consumption per adult equivalent is then compared to this poverty

line, where the adult equivalents are defined as follows:

<1 1-3 4-6 7-9 10- 13- 16- 20- 40- 50- 60- 70+

12 15 19 39 49 59 69

0.41 0.56 0.76 0.91 M: M: M: 1.00 0.95 0.90 0.80 0.70

0.97 0.97 1.02

F: F: F:

1.08 1.13 1.05

The main issue of controversy here is whether the food threshold of 2,500

kcals/day is appropriate. For instance, a recent World Bank mission to Rwanda

(May 4-12, 2016) recommended lowering the calorie threshold to 2,150 kcals

per day, presumably on the grounds that this is more in line with practice

elsewhere, particularly in the region.

The WHO (1985) finds that the daily energy requirement for a moderately

active man (1.6 times basal metabolic rate) weighing 65 kg is about 2,700 kcals

per adult, or possibly slightly less in the tropics. The FAO sets a lower limit for

those who are undernourished – about 2,270 kcals. Given the current age and

demographic structure, and the NISR weights shown above, this implies an

average consumption of about 2,066 kcals per capita, in line with practice

elsewhere (e.g. 2,100 kcals in Vietnam).

Caloric thresholds, and adult equivalence scales, vary widely from country

to country, making comparisons across countries difficult.

6. Conclusion

It is clear that the measurement of (monetary) policy is a technical intricate

process, and different assumptions can lead to somewhat different

conclusions about the pattern and changes of poverty rates.

Moreover, there are other very different ways to measure poverty,

including versions of the increasingly popular multidimensional poverty index

(e.g. Wang et al. 2016; Rwanda 2018b), or indexes based on a stripped-down

set of indicators (e.g. Pogge and Wisor 2016). And surveys themselves are

rarely very accurate (see Beegle et al. 2016).

Given how hard it is to measure poverty, it should be no surprise that it

will be difficult to determine when we have indeed achieved a world without

poverty, but the wider use of best practices in measuring autoconsumption,

deflating, applying adult equivalences, and setting poverty lines would

certainly be welcome.

161 | I S I W S C 2 0 1 9