Page 136 - Invited Paper Session (IPS) - Volume 1

P. 136

IPS115 Reija H.

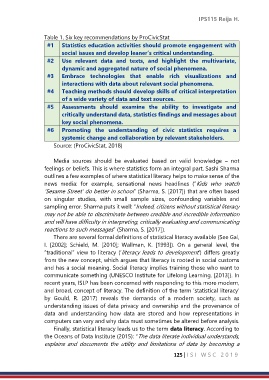

Table 1. Six key recommendations by ProCivicStat

#1 Statistics education activities should promote engagement with

social issues and develop leaner’s critical understanding.

#2 Use relevant data and texts, and highlight the multivariate,

dynamic and aggregated nature of social phenomena.

#3 Embrace technologies that enable rich visualizations and

interactions with data about relevant social phenomena.

#4 Teaching methods should develop skills of critical interpretation

of a wide variety of data and text sources.

#5 Assessments should examine the ability to investigate and

critically understand data, statistics findings and messages about

key social phenomena.

#6 Promoting the understanding of civic statistics requires a

systemic change and collaboration by relevant stakeholders.

Source: (ProCivicStat, 2018)

Media sources should be evaluated based on valid knowledge – not

feelings or beliefs. This is where statistics form an integral part. Sashi Sharma

outlines a few examples of where statistical literacy helps to make sense of the

news media: for example, sensational news headlines (“Kids who watch

‘Sesame Street’ do better in school” (Sharma, S. [2017]) that are often based

on singular studies, with small sample sizes, confounding variables and

sampling error. Sharma puts it well: “Indeed, citizens without statistical literacy

may not be able to discriminate between credible and incredible information

and will have difficulty in interpreting, critically evaluating and communicating

reactions to such messages” (Sharma, S. [2017]).

There are several formal definitions of statistical literacy available (See Gal,

I. [2002]; Schield, M. [2010]; Wallman, K. [1993]). On a general level, the

“traditional” view to literacy (‘literacy leads to development’) differs greatly

from the new concept, which argues that literacy is rooted in social customs

and has a social meaning. Social literacy implies training those who want to

communicate something (UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning. [2013]). In

recent years, ISLP has been concerned with responding to this more modern,

and broad, concept of literacy. The definition of the term ‘statistical literacy’

by Gould, R. (2017) reveals the demands of a modern society, such as

understanding issues of data privacy and ownership and the provenance of

data and understanding how data are stored and how representations in

computers can vary and why data must sometimes be altered before analysis.

Finally, statistical literacy leads us to the term data literacy. According to

the Oceans of Data Institute (2015): “The data literate individual understands,

explains and documents the utility and limitations of data by becoming a

125 | I S I W S C 2 0 1 9